Glacier's Make-up

Even glaciers wear make-up – according to the American glaciologist Robert Sharp from Caltech Institute of Technology in Pasadena/California. Here he´s referring to the conspicuous dark stripes or the zigzag patterns of stone rubble, a predominant characteristic of the ice masses in mountain glaciers.

How these striped patterns emerge can be clearly seen on the massive ice tongue of the Barnard glacier in the St. Elias Mountains in Alaska. Every ice flow from the side merges with the main flow in the valley and widens it – and the rubble on the edges of the inflows, the lateral moraines, form medial moraines in the main flow.

Impressive, winding medial moraines are transported down the valley on the back of the largest ice mass in the Alps, the 22 kilometre long Aletsch Glacier.

Right up on the glacier below the prominent 4000 metre peaks of the Jungfrau and Mönch mountains you can see how the medial moraines of the Aletsch are formed. Three large, relatively flat ice fields converge here in a gigantic ice plateau, the Konkordiaplatz.

The rubble that crashes down from the ice free ridges on to the edges of the three large ice fields collects in so-called lateral moraines. This rubble is constantly drawn down by the ice on its way down the valley. This way bands of stone rubble form in the middle of the massive ice tongue of the Aletsch glacier – lateral moraines merge into medial moraines.

The ice at the Konkordiaplatz gets pushed downhill at a speed of almost 200 metres per year, half a metre per day!

-

Cracks emerge in the flow ... -

... melt water collects in the crevasses.

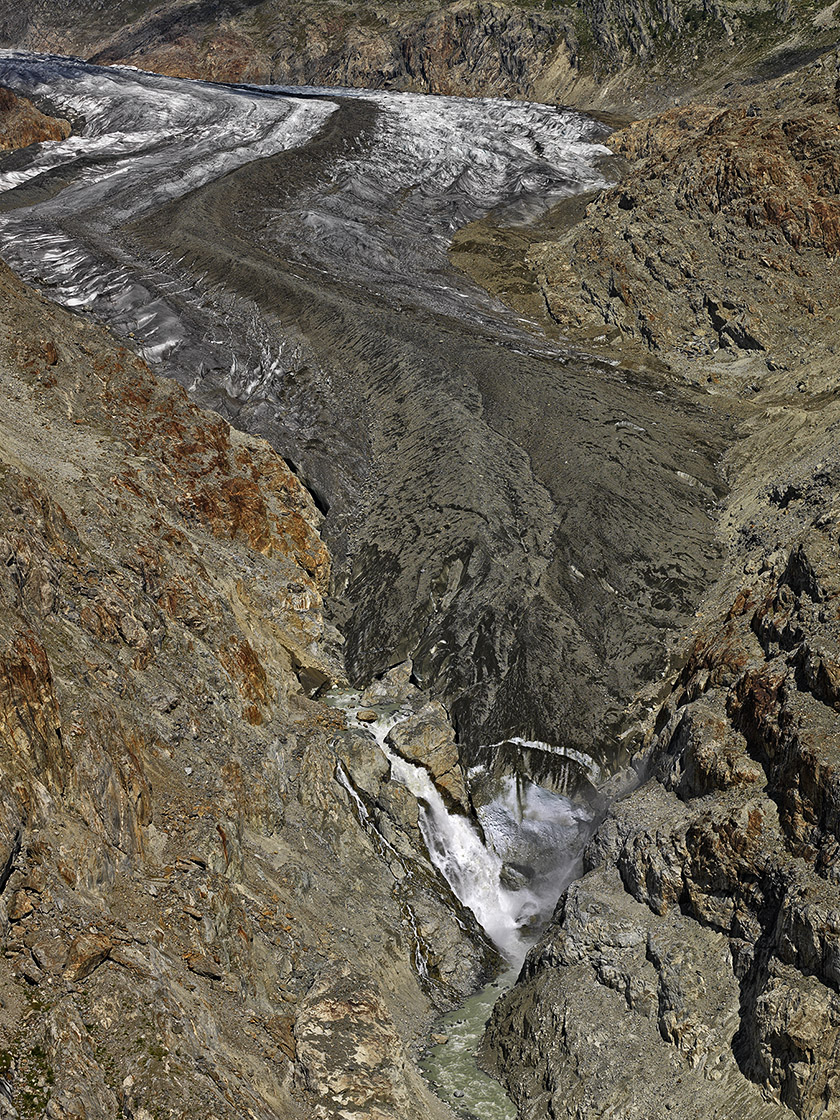

At the end of the ice tongue, where the glacier pushes its way into the Massa gorge and the ice melts, the rubble is compressed to such an extent that the glacier ice below is hardly visible.

The Aletsch glacier like most of the earth´s glaciers is suffering from climate change, too. At its thickest point at the Konkordiaplatz the ice is shrinking by roughly one metre per year and its tongue is shortened by an average of 23 metres per year. Since 1860 its length has been shortened by about four kilometres. The effect of the rubble on its ice tongue is not yet known.

In addition to stripes of moraine rubble the surface of the Malaspina glacier in Alaska manifests unique zigzag patterns. This glacier spreads like a huge, flat pancake over the coastal plain between the St. Elias mountains, over 5000 metres high, and the Pacific coast. It is the largest piedmont glacier on earth with an area of 3000 square kilometres, larger than the Saarland (2570 square kilometres).

25 glacier tongues flowing out of the mountains converge. From their origins in the mountain valleys almost all of them carry on their backs straight or twisting medial and lateral moraines.

However, as soon as they slide into the foreland they collide with the other glacier tongues which are all creeping forward at different speeds depending on the push from the mountains behind. Now the glacier tongues push forward “peacefully” side by side or they get in each other´s way or meet with obstacles below the surface. This slows them down.

The result: the original elongated moraine tracts get pushed together forming curves and even zigzag lines. A weird pattern emerges, as the gigantic ice cake pushes towards the coast where it gradually disintegrates and melts. The rubble remains or gets washed into the sea by the melting water.

By the way: using satellite pictures the geologist Dirk Scherler from the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam is currently collecting data with Swiss colleagues on rubble cover on glaciers worldwide. Even a ten centimetre thick layer of rubble can prevent the glacier ice from melting– and can therefore have an effect on the retreat of the ice giants caused by climate change. Findings from this research aim at improving measurements of the shrinking glaciers caused by climate change.

No comments